Digital advertising has never been more complicated than it is right now, and it is likely to only become more so. There are continually more and more layers and stakeholders being added and it can seem like a lot to keep track of.

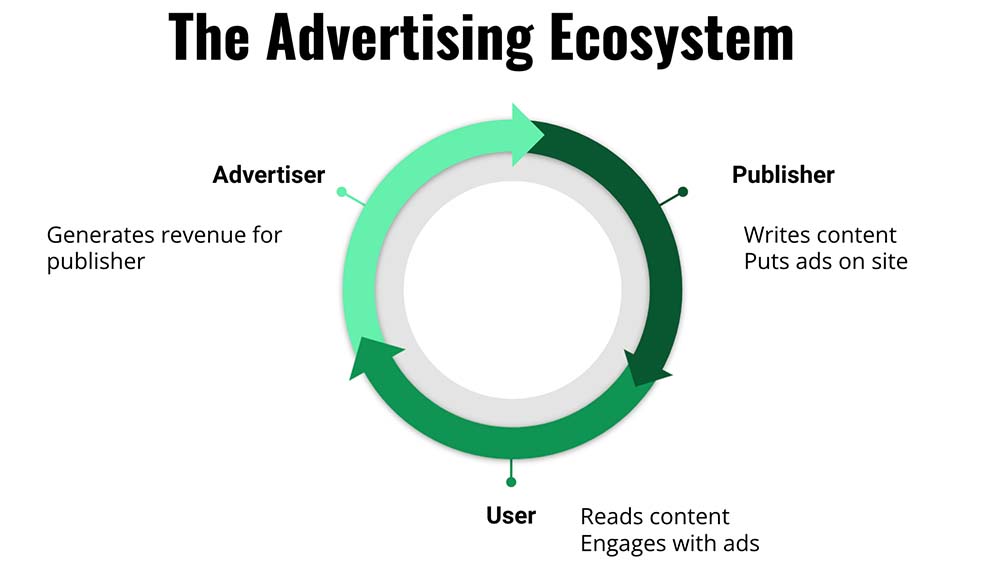

However, even though digital advertising is becoming so increasingly intricate, there are three main components in the ecosystem that remain the same: the publisher, the advertiser, and the user. The relationship between these three elements is ultimately what drives the advertising ecosystem.

We recently hosted a webinar on the ad ecosystem and adops. You can watch the recorded webinar here.

A short history of the advertising ecosystem

The relationship between advertisers and publishers used to be very straightforward–an advertiser would want to advertise on a publisher’s website and then the publisher would charge them whatever they saw fit or negotiated with the advertiser. After some time, brands and advertisers wanted to get a bit more granular to the types of people they were advertising to, such as targeting specific age groups or user locations. This is when things began to get more complicated.

To handle the intricacies of this type of targeting, different technologies had to be developed. This is where DSPs and SSPs come in:

DSP (Demand Side Platform): for brands and agencies for overall campaign management, such as budgeting, targeting, and bidding. DSPs provide management of advertising across multiple RTB (real-time bidding) networks. Some companies include Amazon Ads, Quantcast, and Amobee.

SSP (Supply Side Platform): for publishers to supply their inventory more effectively to advertisers and brands. This allows publishers to get their inventory out to a wide array of advertisers, earning the most possible money for that ad space. Popular ones include AppNexus, Pubmatic, and Amazon Publisher Services.

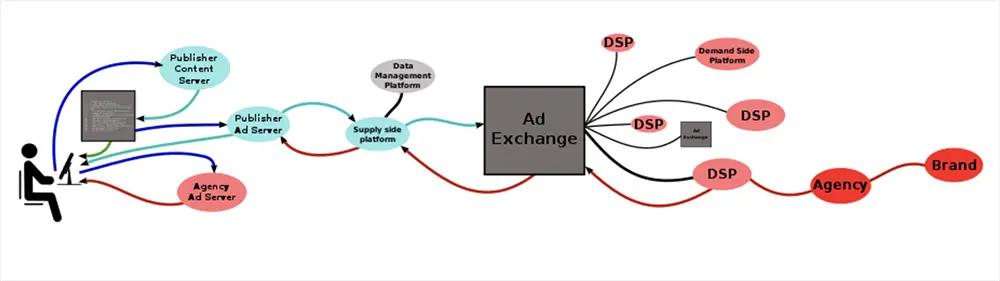

Below is a diagram of how DSPs and SSPs fit into the advertising ecosystem. On the right, we have brands who work with agencies, who then use DSPs within an ad exchange. There are multiple DSPs that go into an ad exchange.

On the left-hand side, we have the publisher, who is creating content. They are working with an ad server, which then uses the different SSPs. SSPs are simultaneously being plugged into data management platforms to help identify some of those key targets of what advertisers are trying to bid on.

Both SSPs and DSPs then work within the ad exchange to locate the correct inventory and sell it to the advertiser. Some top ad exchanges you may have heard of include Google Ad Exchange, Rubicon, and OpenX. Where supply and demand meet is the then agreed-upon price.

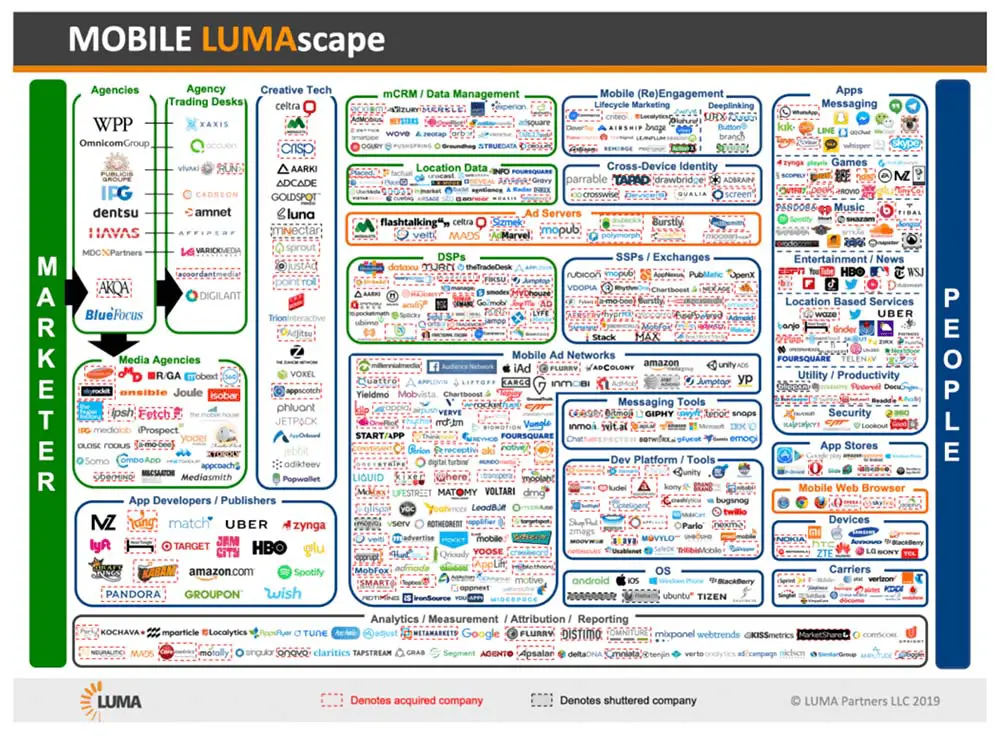

Unfortunately, this is just a smaller piece of a larger puzzle. Below, we have the Display Lumascape, which tries to lay out how exactly display advertising works. As you can see, it is exceedingly complicated and has since actually even grown and become more intricate since it was developed.

Luckily for publishers, this is all automated and happening behind the scenes. Publishers do not need to be a part of the bidding process, but having a general understanding of how the ad ecosystem works can help you understand where your revenue is coming from.

How the bidding process works

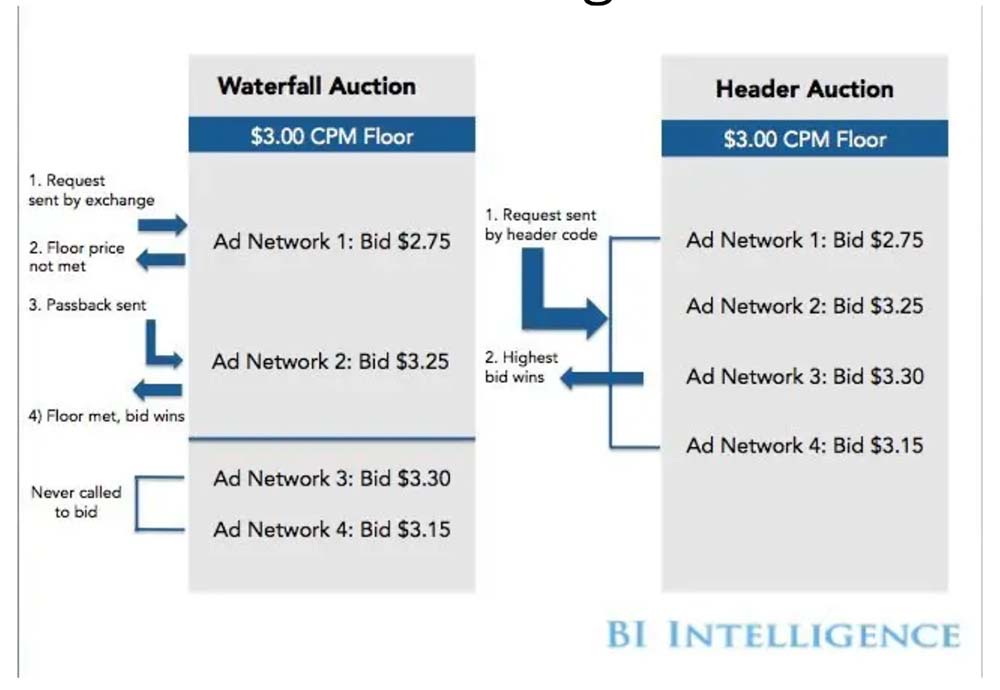

Originally, there was what is called a Waterfall Auction. When the ad tech first came out, we wanted these different players to be able to compete for particular advertising spaces versus just providing it to one advertiser. To start, a floor would be set for the CPM (cost per mille–or thousand–visitors). If, for instance, the floor is $3.00 and Advertiser 1 bids $2.75, that ad would not fill. Now, advertiser 2 bids $3.25; this advertiser bid above the floor price, so they would fill that ad space.

However, this method left money on the table. Because the ad inventory would fill with whoever bid above the floor price first, it meant that other bids didn’t have the chance to win. There could have been Advertiser 3 who would have bid $3.30, but since that space was filled by Advertiser 2 at $3.25 right when they bid above the floor price, the publisher loses out on advertisers that may have paid more.

This is when header bidding came into play. In this header auction example, all four advertisers were able to participate in the bidding process at one time. Advertiser 3 is the highest bidder, so they would fill that ad space.

Header bidding actually happens on the page that has the ad inventory. When header bidding began, Google became involved and created Google EBDA, or Google Exchange Bidding Dynamic Allocation. This is Google’s server-side alternative to header bidding, rather than having the auction happen on the page.

In this example, we have different DSPs and networks that are then running in the exchange auction before it shows up on the page. This is different from Google AdSense and Google Exchange and is a separate auction that is working with different SSPs that are then being fed by the DSPs.

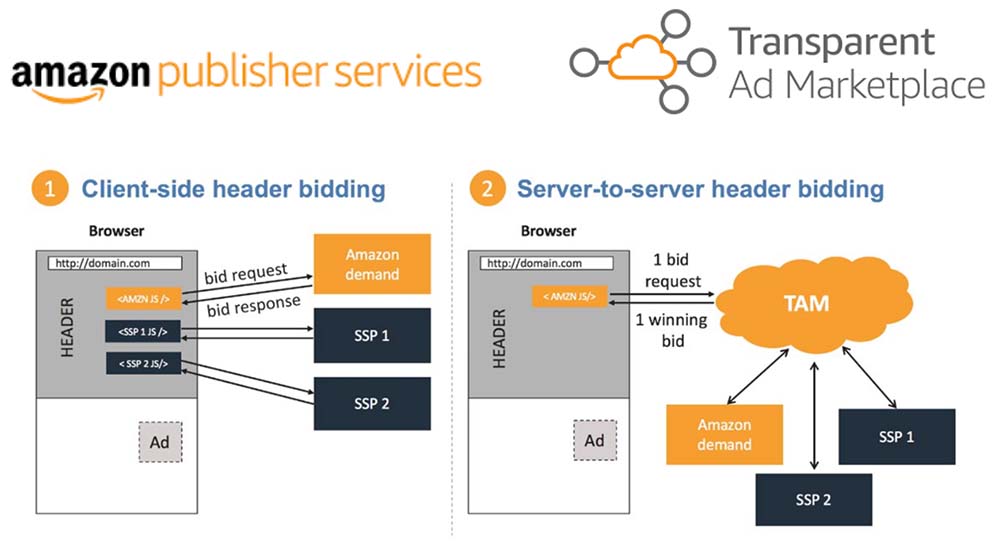

Once Google created EBDA, Amazon also became involved. At this time, Amazon was just acting as an SSP. To compete with Google, Amazon created the Transparent Ad Marketplace. Now, Amazon is also running a server-side auction to then put forth their best bid to run client-side. Those that have Amazon demand should also be using Amazon Transparent Ad Marketplace so that you will get your highest bid from Amazon.

At this point, there are multiple auctions happening at once. There is Google running their own demand, Google EBDA putting forth their best bid from their own auction, Amazon putting forth their best bid from their own auction, all of which are competing against header bidders we believe are the best for the site so that we get the highest-paying ad in that space.

Because there are so many parties involved in getting ad inventory filled, it’s difficult to continue that original transparency within the ad ecosystem. Ads.txt (Authorized Digital Sellers) was created as a way for publishers to securely declare who is authorized to sell their inventory; this is now required by Google MCM (Multiple Customer Management), which Ezoic is a part of. Ads.txt helps weed out bad actors that are trying to fraudulently take advantage of the bidding system for their own benefit.

While ads.txt is a publisher-focused file, sellers.JSON is for SSPs and exchanges. Sellers.json is also publicly accessible and is a file that contains details on the inventory they can sell. These two files together are able to identify the final seller and publishers can verify if an SSP has a valid relationship with them.

How to benefit from understanding the advertising ecosystem

How you operate within the ecosystem can greatly affect your site’s performance. Now that we know how the advertising ecosystem works, we can better navigate how to benefit from it.

Changing the variables will affect what advertisers see in the bidding process and impact the way they bid. This includes ad locations, sizes, colors, etc. For example, if you allow a 300×600 ad size for all users instead of a 300×250 sidebar ad, it can affect the future viewability and CTR (click-through rate) of the ad units underneath it. Because of this, you will want to choose the optimal situations to allow that larger ad size.

Two important elements of this testing are the number and size of the ads because of something called ad dilution. All ads have the ability to dilute one another because they are all competing for the user’s attention. Too many ads or too big of ads will draw their attention away from other ads on the page. Advertisers look at the bidding history of a site and its overall ad performance; if users are bouncing or not scrolling to see other ads because they were affronted by larger ads or too many ads, advertisers will bid less on that ad inventory because it continually performs worse and worse. Over time, this devalues your ad inventory, ultimately making you less money and hurting UX.

We see this happen a lot when Ezoic customers leave and go to another provider; that provider may jam a bunch of ads without considering how those ads dilute one another. Initially, the publisher will earn a lot of money because of the positive ad performance history; advertisers see that this site has performed well in the past and now they are bidding on all of the new ads on the website.

But over time, as those ads get clicked on less and less and users bounce more frequently, that performance will decline and continually make the value of your ad inventory decline. Then, the only way to increase earnings is to put more ads on the page. This may increase revenue for the time being again but it will continue to lessen the value of the ad inventory, ultimately continually lessening the value of your site.

This is where Ezoic’s ad testing comes in. We’ve discussed this before in a previous blog, but it’s important to understand that you, as the publisher, have complete control over your ad inventory. One of the best ways to profit from your ad inventory is to optimize your ads for individual users. Ezoic is constantly changing the variables of the ad inventory with artificial intelligence, finding the best combination of ads for each visitor. This means that as Ad Tester continually tests locations, sizes, colors, etc. of ads, it gets smarter and smarter about what a particular user would like to see. Over time, this improves UX and increases your earnings.

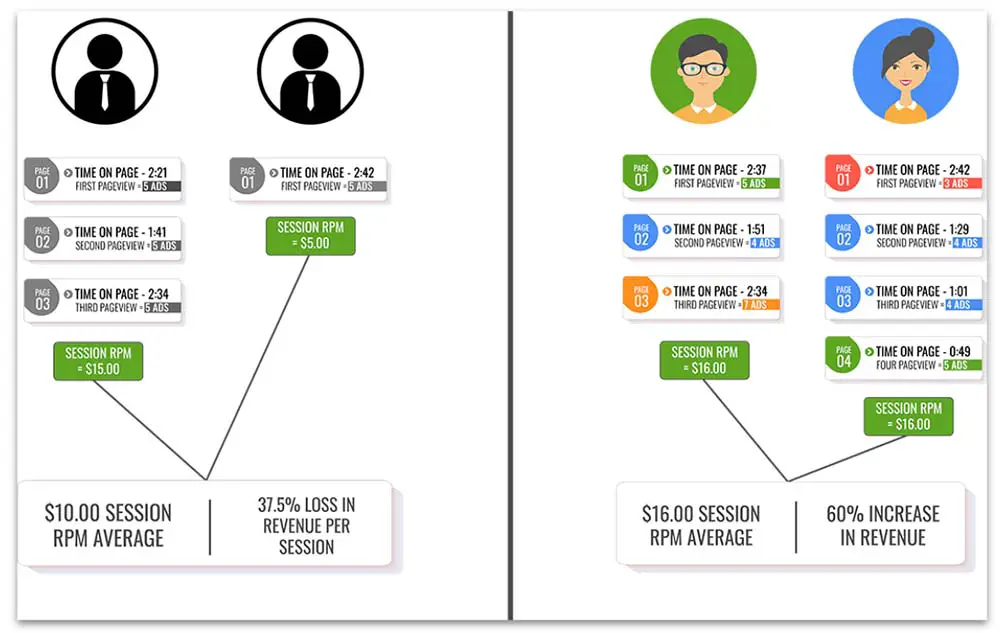

Ezoic uses session revenue when measuring earnings, or EPMV (earnings per thousand visitors) rather than RPM (revenue per thousand impressions) or CPM. This is because it gives a better view of the overall health of a website rather than just the performance of a particular page. It’s great when a certain page is performing well, but if users don’t visit more pages with more ads after visiting that page, then there’s money being left on the table.

For example, let’s consider two different users. On the left, we have a user that visited one page and saw five ads, went to another page and saw five ads, and then went to another page and saw five more ads. The session RPM of this first example is $15.00 on average. However, another user visits that same first page and then bounces; their session RPM is $5.00. This means the average session RPM of the site was $10.00.

Now let’s look at the right side of the diagram. There is the same first user that didn’t mind that there were five ads on the first page and they move on to another page of the site, where they see four ads. Just like before, they move onto a third page, but this page has seven ads. This means that instead of seeing 15 ads, the user saw 16 ads, increasing the session revenue to $16.00.

Looking at the second user, they bounced originally when there were five ads. However, if we showed only three ads on the first page, they were inclined to visit even more pages of the site. Now, that user visited another page that had four ads, went to another page with four ads, and then visited another page with five ads. This also adds up to $16.00 in session revenue, meaning the site’s session RPM is at an average of $16.00. You now have a 60% increase in earnings. This is exactly what Ezoic’s technology is designed to do.

Putting it all into practice

The advertising ecosystem has gone through many changes since it first began in the 1990s. There are more things to keep in mind and hoops to jump through than pioneer publishers ever had to deal with. However, publishers now also have more opportunities than ever to make money from advertising on their website.

While there are many ways to improve your earnings and UX, focusing on improving your ad inventory is one of the most important things you can do. This includes making sure you have the right actors in play, such as using an ads.txt file, and ensuring you’re working with a partner that correctly implements a seller.json file. It also means optimizing all of the potential ad locations on your site so that you are getting the highest session revenue possible.